The Anglo-Saxons arrived in the fifth century and Litlington’s origins likely date from then: a typical linear Saxon village built above flood level. There are various published guesses at the name’s meaning. The most convincing suggests it evolved from ‘the place where Lytel has his homestead’, the ‘ing’ meaning ‘the place of’, and the ‘ton’ meaning farmstead or homestead.

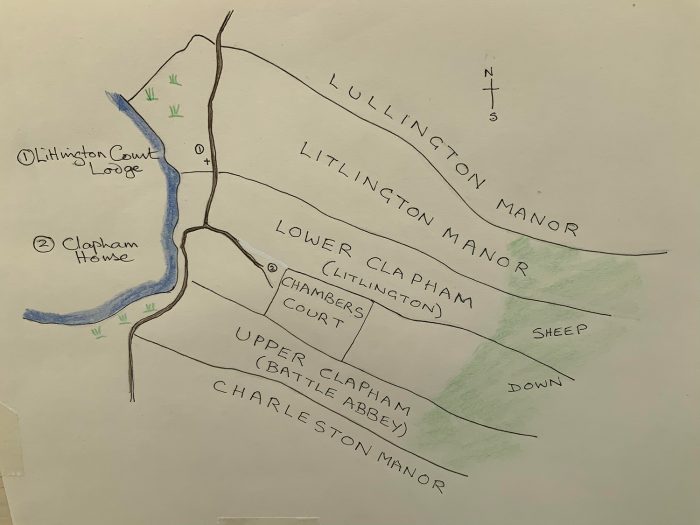

The medieval manor of Litlington and Lower Clapham lay between Battle Abbey’s Cuckmere manors of Lullington and Upper Clapham. Litlington is first recorded as belonging to the one-time Saxon minster church (or monastery) of Bishopstone. After the Norman conquest all property was taken into the hands of the Crown; the Bishop of Chichester as head of the diocese held Bishopstone’s Litlington lands from the King. Being part of Bishopstone, Litlington was not mentioned by name in the Domesday Book of 1086. At this time, it was a collection of agricultural units expressed in hides, a hide being a Saxon measure of land needed to sustain one family. In Sussex this was usually reckoned to be 120 acres. Nearly 100 years after the Conquest, in 1148, those Saxon boundaries were still in use when a man called William Burdard handed back ‘10 hides of land in Littleton and Clapham’ to the new Bishop of Chichester Cathedral, Bishop Hilary, owing him 100 marks in silver for occupying them. William Burdard had, officially or not, been collecting monies from under-tenants that were due to the Church and then failed to pass them on to Chichester. It seems likely that Burdard, having once been installed as a monk in this distant location, had grown elderly and complacent. Bishop Hilary forgave the debt and granted Burdard the tenancy for the rest of his life but only on condition that he wear secular dress. He was effectively de-frocked and became tenant of the land rather than representative of his Chichester overlords.

It is significant that this record is so close to the earliest given for the parish church of St Michael the Archangel (c.1150). The issues raised by the Burdard affair might well have provoked a complete reappraisal of the particular circumstances of Chichester’s distant assets in Litlington and Lower Clapham which were still untidily defined by their Saxon origins. The building of a new (stone) church with a dedicated priest would make possible a formal separation of Church from manor. It would end an out-dated, pre-Conquest relationship between minster (or monastery) and one of its field churches, replacing it with the Norman, feudal relationship of lord and tenant. It would also offer the opportunity formally to establish the extent of a Parish of Litlington that included all the Church’s land between Battle Abbey’s manors of Lullington and Upper Clapham. In this one document from 850 years ago we can perhaps see Litlington gain a stone-built church, a priest, a parish and the beginnings of a new manorial structure.

In 1205, the Cartulary shows the two five-hide properties that formed the lion’s share of the new parish as held by Simon de Chelsfield and Reginald de Clifton. They held the properties by knight service, a feudal land tenure in exchange for military service. Within the boundaries of the parish there was another holding of two hides (later known as Chambers Court) situated behind present day Clapham House, but this was always tenanted separately from Litlington.

From the fourteenth century there are few surviving local records, particularly in the first half, as famine, French raids and the Black Death ravaged the south coast into the 1370s. However, from Chichester’s records of tithes due from each parish we get a glimpse of life there in 1341. Litlington’s value to Chichester was said to be £10 a year most of which was accounted for by sheaves (of corn, wheat or barley) and a comparatively small amount for wool and lambs. Litlington’s Glebe assets included a house and garden for the rector with its own pigeonry. Other produce the authorities considered titheable in the parish were listed as hemp and flax, milk, two further pigeonries, calves, porkers, geese, eggs, hay, beehives and gardens. The specific mention of gardens suggests Litlington has always been good fruit-growing land. Indeed, one of the family names to appear in the earliest court rolls is that of Garden or atte Gardyne.

As records become more numerous and we are able to rejoin the story in the late fourteenth century, the lords of Litlington were the Lecche or Leche family who held both five-hide holdings as one manor. The manor courthouse for Litlington lay at the heart of a manorial complex, on the site of today’s Church House Farm. Here Litlington’s tenants had to swear fealty, report infringements of the law, seek justice, and pay rents and fines. Apart from Litlington manor’s demesne land, it administered the smaller farming estates that made up Lower Clapham: three separate ‘freehold’ tenancies no more than 60 acres with a farmstead, and limited grazing on the downland. The lords of Litlington manor also held the advowson, or, right to present clergy to the living. In 1450, Roger Leche, gentleman and lord of Litlington manor, was among five other local men pardoned for their involvement in the Cade uprising. This popular uprising in the South East was the largest in England during the fifteenth century and every village in the Cuckmere region sent representatives. It was a revolt against bad governance, corruption and military losses in the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), when the French throne was claimed by Edward III.

The ‘a Lye’ or Legh family were the next to hold Litlington manor and advowson. In 1461, Roger Legh inherited from the Leches, almost certainly by marriage, and in 1478 was among the men doing homage to the manorial lords at Chichester for lands held in Litlington by knight service. However, by this point, homage was a token gesture to the overlord as such manors were effectively freehold estates exchanged by charter or conveyed by will. Richard Legh’s daughter, Joan, married John Rootes of Buxted. Members of the Rootes family were to remain lords of Litlington manor for over 100 years, although Joan was the last to actually live there. For 200 years, this branch of the significant Sussex Rootes family of lawyers and landowners leased or bought or acted as feoffees of land throughout the Cuckmere. If not always at the same time, besides the hundreds of acres of Litlington and Lower Clapham, they had the manor of Exceat, two manors at Chyngton, and Dean’s Place in Alfriston.

Once Joan Rootes had died her son and heir, William Rootes of Uckfield, was happy to lease out and even to sell off parcels of his Litlington property. The manor farm of 300 acres, including downland grazing and outlying meadows, was let first in 1538 to Richard a Chambre (of the Chambers Court family). The earliest detailed description, dated 1644, refers to ‘The Courtlodge of Litlington’ comprising a messuage (a feudal term for a dwelling house with outbuildings and land), pigeon-house, garner, two barns, stable, stall, buildings, gardens and orchards. Much of the curtilage (boundaries) of the manorial complex can still be seen today in the standing walls around Church Farm.

Meanwhile, one of the tenants of a small farm estate in Lower Clapham called John a Broke was about to begin a process that would radically reconfigure ownership of the whole parish. He was first recorded as a freeholder in Lower Clapham in 1478. The Broke (or ‘a Broke’) family was a significant presence in the valley from the fifteenth century onwards, acquiring much property and land. They had a long lease on Battle Abbey’s manor of Upper Clapham (abutting Litlington’s Lower Clapham to the south) and a national tax assessment in 1524-5 shows their local significance unmistakeably. Richard and John Abroke senior were assessed at £50 and £60 respectively and John Abroke junior also at £60. These were the highest assessments in the area with the majority of Litlington residents assessed at just £1 apiece. Richard and the older John were clearly men of status in the Cuckmere valley, overseeing disputes in the Lullington court records in the first decade of the 1500s. It is likely to have been the younger John who began to acquire some of the workers’ cottages in Litlington’s ‘street’ as well as more small parcels of land in Clapham. In 1523, he was the object of a raid on his dovehouse organised by a small resistance force against landowners who tried to enclose commonly held land for their own profit. John took a 60-year lease of Frog Firle in 1529. In 1536, he bought a moiety (or half) of the manor of Charleston. At his death in 1543 his eldest son William inherited. He and his descendants continued the expansion. In 1597, his daughter Jane reunited Charleston Manor, by buying the remaining moiety, and his grandson purchased the neighbouring Clapham Manor House and combined Upper and Lower Clapham into one estate. 160 years later, subsequent owners, the Beans, would buy up the manor and advowson of Litlington, and for a while at least, the lords of Clapham Manor House owned the whole of Litlington.

The Clapham House Estate

In the late seventeenth century, Henry Bean, a tenant farmer from East Blatchington, just outside Seaford, took on the tenancies of two manorial holdings in Litlington: Upper Clapham and Lower Clapham. Together, these two farms would be developed into a substantial farming estate during the eighteenth century by Henry Bean’s son and grandson: John Bean Snr. and John Bean Jnr.

Upper Clapham (or Clapham manor) was a strip of land that lay between the parishes of Litlington and West Dean but belonged to Lullington Parish. In the Middle Ages it had been the property of Battle Abbey, as part of its Lullington estate. Lower Clapham (or Clapham House and farm) was mainly situated in Litlington Parish (see medieval manorial plan above). According to amateur family historian Trevor Griffin, when Henry Bean took over the tenancies of Upper and Lower Clapham in the 1690s, combined they provided 570 acres of water meadow, pasture, arable and sheep down. Henry and his wife Mary raised their four sons in the comfortable surroundings of Clapham House. Following Henry’s death in 1702 his son, John Bean Snr., and later his grandson, John Bean Jnr., began assembling the Clapham Estate by gradually acquiring properties and parcels of land in the village and its surrounds as they became available. Griffin dates their most notable acquisitions as follows: Lower Clapham (Clapham House and farm) in 1719; Upper Clapham Farm in 1736; Charleston Manor in 1748; and the manor of Litlington in 1756. In 1757 the manor of Litlington was merged into the Clapham estate.

Charleston Manor was the most significant property the Bean family ever owned. Recorded in the Domesday Book as owned by Ralph the Earl and later held by Alured, William the Conqueror’s Cup Bearer, the house has been dated to 1090/1100. It has a Romanesque window of this period, making it one of the oldest surviving domestic properties in the country. The dovecote is also of the Norman period. The house was extended in the fifteenth century and the great Tithe Barn was built. The existing frontage and distinctive stable block with its wooden tower were completed just prior to John Bean purchasing it.

The manor of Litlington was also a substantial purchase consisting of Church Farm and various houses in the village, as well as land and properties in Willingdon. This lordship was more significant than those of Upper and Lower Clapham as it included the Advowson (or right to appoint the vicar of the church).

John Bean Snr died in 1749 having accumulated considerable wealth. He had developed his estate at a time of great change in agriculture. He deserted the small highly priced arable plots that had been farmed for centuries in favour of purchasing larger holdings formerly part of monastic estates. He exploited improved farm techniques to put downland to the plough and bred large flocks of Southdown sheep on the remaining downland, which became the leading breed of its day. John Bean Jnr. was 32 when he inherited his father’s estate. He was reputed to be a good farmer and maintained the principles he had learnt from his father. According to Griffin, heJohn Bean Jnr. never married but had two illegitimate children by his housekeeper, Mary Bridgman, whom he employed and lived with until he died. He continued to add to the Bean estate well into his later years, acquiring land in Willingdon, Selmeston, Arlington, Rottingdean, Newick, Chailey, Wivelsfield, Lewes and Brighton. John Bean Jnr. died in 1785 and was buried in Litlington Churchyard. Mary Bridgman was left a malthouse and garden in Litlington for the duration of her lifetime, now a cottage on Clapham Lane. The remainder of the estate was left to his illegitimate son by Mary Bridgman, the third John Bean who found himself a very rich bachelor at 30. Over the course of the early nineteenth century, the estate fell on hard times under the poor management of the third John Bean and his son Felix Bean, a largely absentee landlord. The rural depression following the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) will have contributed to the decline of the Bean Estate. This was a time of severe poverty and unemployment. Protests in and around Litlington included barn burning, the theft of sheep and grain and an orchard of 100 trees felled in one night. In 1830, the Bean estate was sold by Felix Bean, to Reverend Thomas Scutt for £39,500 including stock, carriages and horses. He added Chambers Court Farm, completing the assembly of the Clapham Estate.

In her short history of the Litlington Pleasure Gardens, Mr Russell’s Little Floral Kingdom (1999), local historian Juliet Clarke evokes the village as it would have been over two hundred years ago when the Bean family still owned Clapham Estate:

The village consisted of 20 cottages, the church, the farm and the ‘big house’, Clapham, from which the Bean family had dominated village life as long as anyone could remember. The roads, not much more than cart tracks, served only to link Litlington to other properties of the estate…, as well as the farmlands between. There was a bridge across the river to Alfriston which had shops, a tannery and a brewery; from there a track led along the foot of the Downs to Lewes, the county town where the biggest local markets and annual stock fairs were held. But in the main, the 100 or so villagers of Litlington inhabited a small, inward-looking world, where daily life revolved around work in the fields and pastures of the estate. At night the occasional tea-smuggling brought extra money in a whispered contact with the outside world but for the most part Litlington was an isolated, almost self-sufficient community, one of thousands like it across the country.

According to Jim and Philippa Foord-Kelcey, authors of Maria Fitzherbert and Sons, it was at this time that Litlington acquired its most famous residents, the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and his unofficial wife Maria Fitzherbert. The late Jim Foord-Kelcey claimed to be a fourth generation descendent of this union and the book is based on information passed down by descendants rather than verifiable documentary evidence. According to the Foord-Kelceys, the Prince of Wales (later George IV) and Maria Fitzherbert bought Clapham House in 1786 under the assumed names of Mr and Mrs Payne. However, there’s no evidence to support a sale of `Clapham House at this time. If they did spend time there, it is more likely the house was leased from the Bean Estate, or maybe just ‘lent’.

In 1785, Maria and George had secretly contracted a marriage, but this was unlawful, breaching both the 1701 Act of Settlement (which forbade Catholics and spouses of Catholics from becoming monarchs) and the Royal Marriage Act of 1772 (requiring the King’s consent to the marriage). Over the next ten years the couple kept a succession of houses where they could live their unofficial lives. According to the Foord-Kelceys, Clapham House was the first of these homes where two of their alleged seven children were born. They also spent much of their time in Brighton between Steine House (Maria’s residence) and the Royal Pavilion (the Prince of Wales’ extravagant seaside palace) which together formed the heart of fashionable society in Brighton. During their early years in Clapham House, the Foord-Kelceys maintain that the couple were very happy and in love. If a royal household was indeed in residence at Clapham House, the villagers of Litlington would have welcomed the extra employment opportunities provided by such a large, wealthy household and grounds and perhaps the chance to learn new skills and broaden rural horizons. It was possibly these skills and influences which trickled down a generation to a young, ambitious gardener from Westdean called John Russell whose orchards and market garden would later become Litlington Pleasure Grounds, a Victorian complex of formal gardens, orchards, a market garden and fine dining.

In 1795, King George III forced his eldest son into a lucrative marriage with Princess Caroline of Brunswick, whom the Prince of Wales disliked. This was the price to be paid for running up the equivalent of £65 million of debt in today’s money. Maria Fitzherbert was dismissed at this time but, after only a year of marriage to Caroline, George sought a reunion with Maria. Maria did not relent until 1799, and only after seeking guidance from both the Pope and the Queen and seeing a will in which George leaves ‘All my worldly property to my Maria Fitzherbert, my wife, the wife of my heart and soul’. George had made this will in 1796, three days after the birth of his daughter Charlotte by Caroline of Brunswick. Maria and George were reunited until 1807 but finally parted in 1809 when Maria had had enough of the Prince’s colourful personality and wandering eye.

George, now George IV, died in 1830. At his request, he was buried with Maria’s eye miniature round his neck. He had also kept all their correspondence. Keen to make amends for her poor treatment by his brother, William IV offered Maria the title of Duchess. Maria refused saying that “she had borne through life the name of Mrs Fitzherbert, that she had never disgraced it and did not want to change it”. But her servants thereafter wore royal livery and she visited the Pavilion regularly. From 1801 until her death in 1837 she lived at Steine House. The Duke of Wellington, to whom she gave a bundle of George’s correspondence for destruction, said she was “the most honest woman he’d ever met”.

Charles Joseph La Trobe (1807-1875) was another prominent resident of Clapham House. La Trobe was a former Colonial Governor in Australia, initially Superintendent of the Port Phillip District (1839-1851) and, later, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Victoria (1851-1854). La Trobe didn’t have the usual background of a British colonial governor. He had no army or naval training and little administrative experience. His family were of Huguenot descent, active in the Church and supportive of the anti-slavery movement. Possibly due to these family connections, in 1837 the British Government sent the young La Trobe to the West Indies to report on measures necessary to prepare the Islands’ slave population for freedom.

La Trobe was a cultured gentleman with high principles and a serious mind. He was a published travel writer with a keen interest in the natural world. The American author Washington Irving, with whom he toured North America, said of him:

He was a man of a thousand occupations; a botanist, a geologist, a hunter of beetles and butterflies, a musical amateur, a sketcher of no mean pretensions; in short, a complete virtuoso; added to which he was a very indefatigable, if not always a very successful, sportsman.

In 1835, La Trobe had married Sophie de Montmollin, the daughter of Frédéric Auguste, a Swiss councillor of state. They had a son and three daughters.

La Trobe’s time as Superintendent of the Port Phillip District was testing. He did not arrive to administer an established colony but rather a dependency of New South Wales whose administration and finances were largely controlled from Sydney. On the two major issues of concern to his colonists – separation from New South Wales and convict transportation – La Trobe was only proactive regarding the latter. In 1849, he defied the Colonial Office and won the approval of his Melbourne colonists by refusing to allow the Randolph to land her cargo of convicts at Port Phillip sending the ship on to Sydney. However, he was more cautious regarding separation, arguing that this was being dealt with in the reorganization plans for all British colonies in Australia.

In 1851, Victoria was finally granted self-government and La Trobe was appointed Lieutenant-Governor. However, the colony had demanded greater powers than it had expertise and resources to manage. When a gold rush hit the colony in the same year, with inadequate policing and funds to manage an influx of thousands of diggers, a crisis ensued. In the end, La Trobe’s inexperience meant he was unable to cope with the immense and rapid expansion of his colony. He resigned at the end of 1852 but wasn’t relieved until 1854. 1854 was also the year that La Trobe’s wife died. Unwell, Sophie La Trobe, had preceded her husband to Europe, returning to her family home in Switzerland. La Trobe returned to England and, a year later, married his wife’s widowed sister, Rose, with whom he went on to have two daughters. La Trobe spent his final years in Clapham House between 1867-1875. He had lost his sight in 1865 preventing him from writing an account of his Australian experience which he had planned under the title A Colonial Governor. He died on 4 December 1875 and was buried at the churchyard in Litlington.

La Trobe was an active initiator and patron of the religious, cultural and educational institutions of Melbourne. Melbourne has La Trobe to thank for its magnificent Botanic Gardens. He also gave leadership, prestige and support to the formation of the Mechanics’ Institute, Royal Melbourne Hospital, the Benevolent Asylum, the Royal Philharmonic, the Public Library and the University of Melbourne.

His widow Rose retired to Switzerland, where a small church, the Chapelle de l’ Hermitage in Neuchatel, was built as a memorial to La Trobe. In 1951, on the occasion of the Centenary of Victoria, a memorial yew was planted in the churchyard in Litlington by La Trobe’s grandson, Captain Charles La Trobe, in the presence of the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Denys Lowson. The parishioners of Litlington commemorate La Trobe’s life every year at a special service on the first Sunday in December, for which the La Trobe Society of Melbourne send flowers from Australia.

Litlington Pleasure Gardens

When the Bean Estate was put up for auction in 1828, the sale particulars include mention of ‘a newly planted orchard in the parish of Litlington…let to John Russell’. Initially, John Russell and his wife Lucy (nee Bartlett) rented Barn Cottage (still standing) and enough land to set up as modest fruit growers and survive the agricultural recession of the 1830s. Of their eleven children, it was their ninth son Frederick (b.1821) who would be the driving force that transformed the burgeoning market garden and orchards into thriving Victorian Pleasure Gardens.

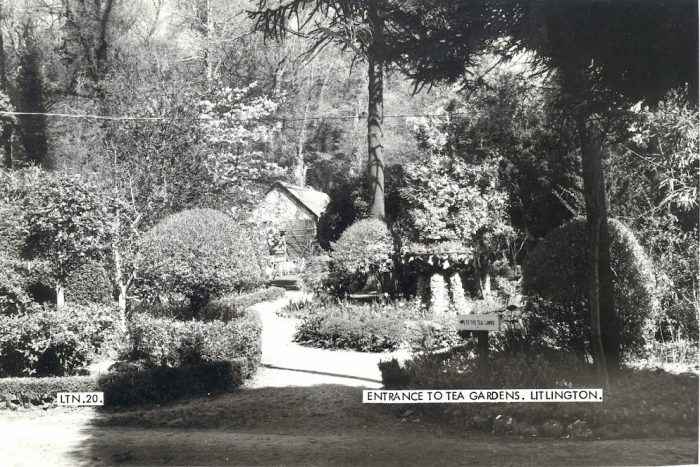

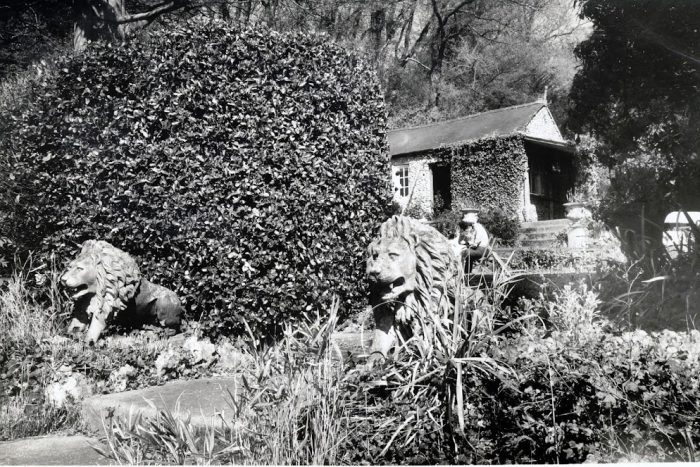

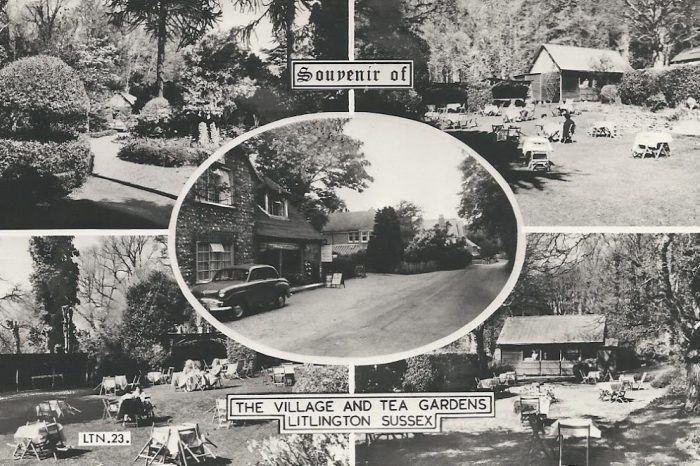

With the help of his siblings and in-laws, Frederick Russell used the expertise he had gained working at the largest nursery in the south east of England (at Lewisham in Kent), plus wealth accrued working for the railways and investing wisely, to expand his father’s enterprise throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Thanks to a succession of Rectors who preferred to live in Alfriston, the Russell family were able to rent Litlington’s Rectory and its glebe land from 1859 to 1893. This was conveniently adjacent to the Russells’ existing orchard and gardens. By 1860, the rural depression following the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) had been replaced by an age of prosperity, fuelled by a rising urban population’s demand for foodstuffs. The growth of railways had seen huge changes in land use as fewer horses were needed, releasing land which had been required to grow feed. At the same time increasing middle-class prosperity led to the construction of villas, each with its own garden. By 1860 East and West Bourne had merged into Eastbourne, a fashionable seaside town attracting the well-to-do in large numbers. They demanded more than accommodation, and a whole new tourism and leisure industry grew up to provide for them. Frederick spotted an opportunity to meet this new demand for food, leisure and decorative gardens. In 1863, he added a 40-foot vinery, a cucumber house, two hot beds, a glass house and a substantial stone entrance featuring a pair of British Lions commissioned from R. Francis, an Eastbourne stone mason. In 1865, Kelly’s Directory recorded ‘extensive fruit and nursery gardens’ in Litlington. The sheer scale of the market garden meant the Russels were likely supplying Covent Garden with baskets of fruit and vegetables transported by rail, as well as local markets in Alfristion and Seaford.

By 1871, the Pleasure Gardens were providing a full catering service in considerable style with starched linen and silver service. Several wooden eating shelters and a pavilion for larger parties had been built. A purpose-built kitchen was also added so that food didn’t have to be lugged uphill on trays from the Rectory kitchen. In 1875, Frederick bought the freehold of a piece of land directly opposite the Pleasure Grounds and built Litlington Hotel (now Litlington House) a substantial property with a glass house attached, separate stabling and a coach house. The entrance to the Pleasure Grounds was moved from beside the Rectory to opposite the Hotel. By 1880, the gardens were fully mature, and the business was thriving. There were swing seats, one could play croquet and cricket and ‘there was good fishing to be had’. Articles in the Eastbourne Gazette praised ‘the mature trees, rich assortment of flowers and shrubs, the pleasantly shaded walks and arbours used for luncheons, teas and dinners’. Visitors would arrive by wagonette, drawn by four horses, along unmade roads and bumpy lanes from Eastbourne, with stops at Willingdon, Polegate and Wilmington so that the churches and other curiosities could be admired. It took about 90 minutes and cost 2/6d, or 3/- First Class.

By 1871, the Pleasure Gardens were providing a full catering service in considerable style with starched linen and silver service. Several wooden eating shelters and a pavilion for larger parties had been built. A purpose-built kitchen was also added so that food didn’t have to be lugged uphill on trays from the Rectory kitchen. In 1875, Frederick bought the freehold of a piece of land directly opposite the Pleasure Grounds and built Litlington Hotel (now Litlington House) a substantial property with a glass house attached, separate stabling and a coach house. The entrance to the Pleasure Grounds was moved from beside the Rectory to opposite the Hotel. By 1880, the gardens were fully mature, and the business was thriving. There were swing seats, one could play croquet and cricket and ‘there was good fishing to be had’. Articles in the Eastbourne Gazette praised ‘the mature trees, rich assortment of flowers and shrubs, the pleasantly shaded walks and arbours used for luncheons, teas and dinners’. Visitors would arrive by wagonette, drawn by four horses, along unmade roads and bumpy lanes from Eastbourne, with stops at Willingdon, Polegate and Wilmington so that the churches and other curiosities could be admired. It took about 90 minutes and cost 2/6d, or 3/- First Class.

In 1882, Frederick died aged 61 without having made a will. The family also lost the Rectory a decade later when a new Rector (Reverend Thomas Fitch) was appointed. Intending to live in the Rectory, he gave the Russells a year’s notice to quit the Rectory and glebe land although he himself was only in office for a year. Luckily Frederick had taken care to put all permanent structures on Nursery not Rectory land. Despite these losses the Russell family continued to run the market garden, the Pleasure Grounds and the hotel until the 1950s and John Russell’s daughter Catherine ran the village Post Office from Well Cottage until the 1930s. In 1924 Clapham House Estate had been bought by Richard Canning-Brown from a direct descendent of Reverend Thomas Scutt, at which point it included Church Farm, the Nursery and Tea Gardens, Rookery Wood and many of the cottages within the village. As the Russell family gradually died out, Litlington Hotel was sold, and the nursery was managed on behalf of the last surviving sisters by Alf Bond. Marjorie, the last of the Russells, died in 1975 aged 82.

Wartime

During the First World War, corrugated iron army huts were erected hurriedly across the country to administer and train troops. One such hut was erected in Litlington on the site of the current village hall. These huts were appropriated after 1918 for many useful purposes such as scout huts, meeting places and village halls. Litlington’s hut became the de facto village hall. In the years following the war, Richard and Maud Brown of Clapham House hosted Christmas parties in the wood-panelled hut (heated with paraffin) and every child was given a Christmas present.

Litlington lost two men in World War I: Harry Constable, Gunner, Royal Field Artillery, and Alfred Ticehurst, Private, 2nd Royal Sussex Regiment.

During the Second World War, one German bomb fell on a pigsty at Clapham House but otherwise the village escaped the war physically unscathed. On 18 September 1943, as part of the war effort, Litlington first held the Clapham Lane Stalls. Fruit and vegetables from Clapham House garden were sold at low prices to buy ‘comforts’ and parcels for the 25 servicemen and four POWs from the village. Over £20 was raised, equivalent to over £900 today. This tradition has been upheld every September to the present with the addition of stalls selling home-made produce, refreshments and bric-a-brac.

After the war, Litlington servicemen were able to choose a thank you gift from the villagers. Several chose a silver teapot inscribed with their name and the message Litlington Thanks You 1939 – 1945, plus a sketch of the village by American War Artist, Rowland Hilder. Hilder lived in Litlington during the war and made several sketches and paintings. These were presented at a party in the Village Hut. Albert Weddle, who won the Military Medal for exceptional bravery in April 1945 while serving in Italy, gave a vote of thanks on behalf of the recipients.

Of the 29 men from Litlington who served in World War II, two were killed: William Douglas Walden, Flying Officer, South African Air force and Richard Drummond-Hay Bucknall, Captain, 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

There is a combined World War I and World War II memorial in Litlington Church.